Supporting Handwriting with Real Script: Take-Aways from Action Research

By Leah Mills

In the spring of 2022, I took a course in Real Script taught by Rebecca Loveless. I was curious to see how this approach would work with some of my more handwriting-averse students, so I set out to research how this program could aid students in improving their handwriting legibility, as well as their comfort while writing and their confidence.

Using an action research method allowed me to remain responsive to student needs, gathering their input along the way. I’ve compiled a few key take-aways and adaptations from this work in the hopes that educators and educational therapists will be able to use this impactful program to benefit a wide range of students, both with and without learning differences.

“Using an action research method allowed me to remain responsive to student needs, gathering their input along the way.”

While writing by hand is not as common as it used to be with the popularization of typing and texting, handwriting is still expected or required in many situations, including filling out forms, using planners, and taking notes. Students who struggle with handwriting are often aware that their handwriting skills are behind their peers and develop their own strategies to compensate. For example, one of my students avoids writing by hand whenever possible, while another has prefaced several writing tasks with a disclaimer that she knows “[her] handwriting is bad; don’t worry about it.” While avoidance and confidence are real issues that students with handwriting challenges face, there are also studies that show perceived poor handwriting carries negative biases that influences students’ test scores (Greifeneder, et al., 2010; Klein & Taub, 2005). The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the decline of handwriting skills, and many teachers are looking for ways to help their students improve this skill, recognizing its importance for tasks across the curriculum.

Real Script

The Real Script handwriting method offers a different approach to handwriting instruction that prescribes pathways for each letter and purports to improve writing fluency and hand pain. Rather than teaching the letter formations of each letter through tracing and copying, students are encouraged to learn the pathways first on their own hand, and then with pen and paper.

Getting Started

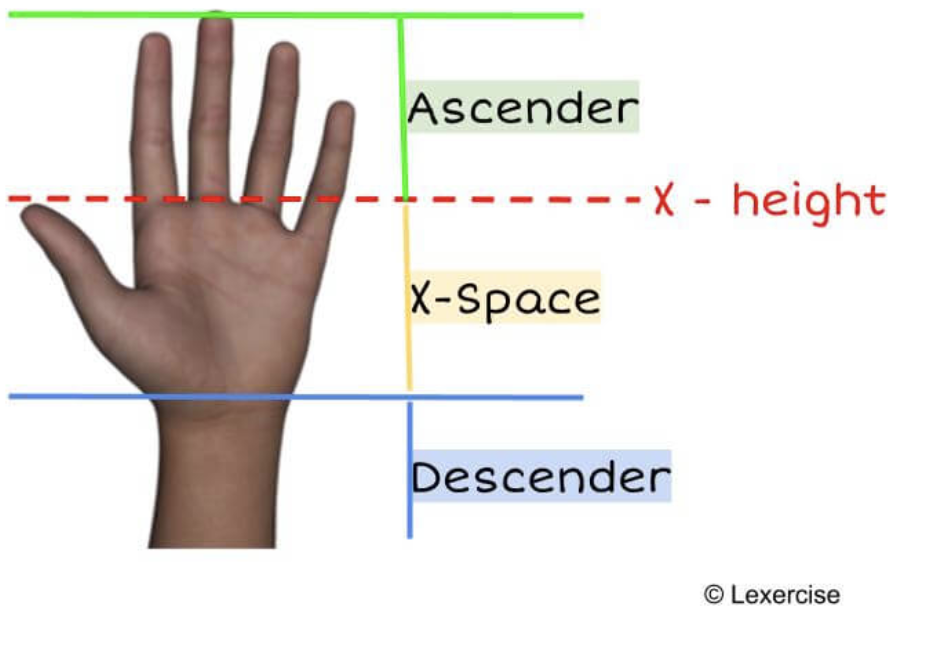

The crease between the palm and fingers on the hand represents the midline, or x-height. The palm area is called the x-space and is where most lowercase letters are made. The area above the x-height is referred to as the ascender, while the area below is called the descender. For example, the pathway for <t> starts in the ascender and moves down to the bottom of the x-space and bounces up, and then crosses at the x-height. Strokes that move from left to right are described as ‘pulling’ for right-handed students and ‘pushing’ for left-handed students, and vice versa for the opposite direction. Try moving your index finger along the x-height of your own palm to get a feeling for why these words are used.

Groups of letters with similar pathways are referred to as emblems–for instance, the vertical downstroke emblem includes the letters <l>, <t>, <f>, <i>, and <j>. Letters with similar pathways are taught consecutively–for example, the <b>, <m>, <n>, <r>, and <h> are all letters that start with a down motion and then a bounce up and over. One aim for this approach is to minimize reversed and rotated letters in decoding (reading) and encoding (writing), since students will form more associations with similar pathways rather than similar looking letters. Real Script also focuses on teaching lowercase letters to start since these are more common (they make up 95% of written text!) and often follow similar patterns.

The Dance of the Pen

Students are taught how to sit while writing, and how to hold a pen so as not to cause pain by gripping too tightly. As students become more comfortable with writing individual letters, they are taught common morphemes and graphemes which can be ligatured, which means connected, such as <ing>, <sh>, and <ed>. When writing words or sentences, students are encouraged to feel the “dance of the pen,” achieving a pleasant flow state. Pens are promoted over pencils to aid in this writing flow. This program has the benefit of being more versatile compared to other methods, in part because there is only a suggested sequence for instruction rather than an established curriculum and workbook like many other programs.

Key Take-Aways

Selecting Writing Implements

In my own research, I encouraged students to use pens when writing which garnered some complaints from students. Pencils are more familiar, they have erasers, and they sometimes give students more control over their writing. I have had the most success introducing pens in the frame of an experiment so that students can test different writing utensils themselves and discover which feels right to them. This also has helped some of my students pay closer attention to the way they hold their pen and how it feels. I’ve also found that markers and whiteboard markers are especially flowy and a nice way to practice letter pathways if pens aren’t enticing enough.

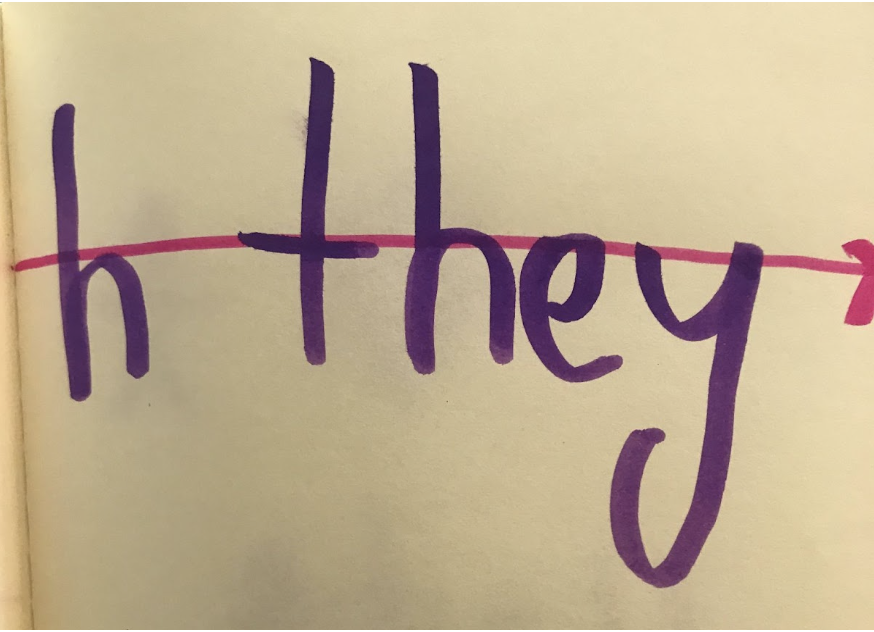

Marking the X-height

Using different colored markers was especially helpful for marking the x-height. When the x-height was drawn using the same pen or marker as the rest of the writing, some of my students often felt the need to intentionally go below or above the x-height so that their writing would all show. This technique was especially helpful for letters that have a cross at the x-height such as <t> and <f>.

Getting Student Buy-in

One aspect of Real Script that many of my students love is the focus on legibility and comfort over “perfectly formed” letters. I’ve found it valuable to discuss the importance of legibility, comfort, as well as fluency with my students. It helps to get their buy-in on why we practice writing letters this way rather than what they’ve been taught or what they’ve gotten used to. For example, we start a <p> at the x-height and go down to the descender and back up - this pathway is not intuitive so students want to know how this way is better than just starting from the bottom. Rather than saying “just because”, we can talk about how it’s easier to make a downstroke than an upstroke, or even test it out ourselves. We can talk about the efficiency of starting at the x-height since the previous letters are usually ending in the x-space. We can also talk about how much easier it is to ligature to the x-height than to the descender.

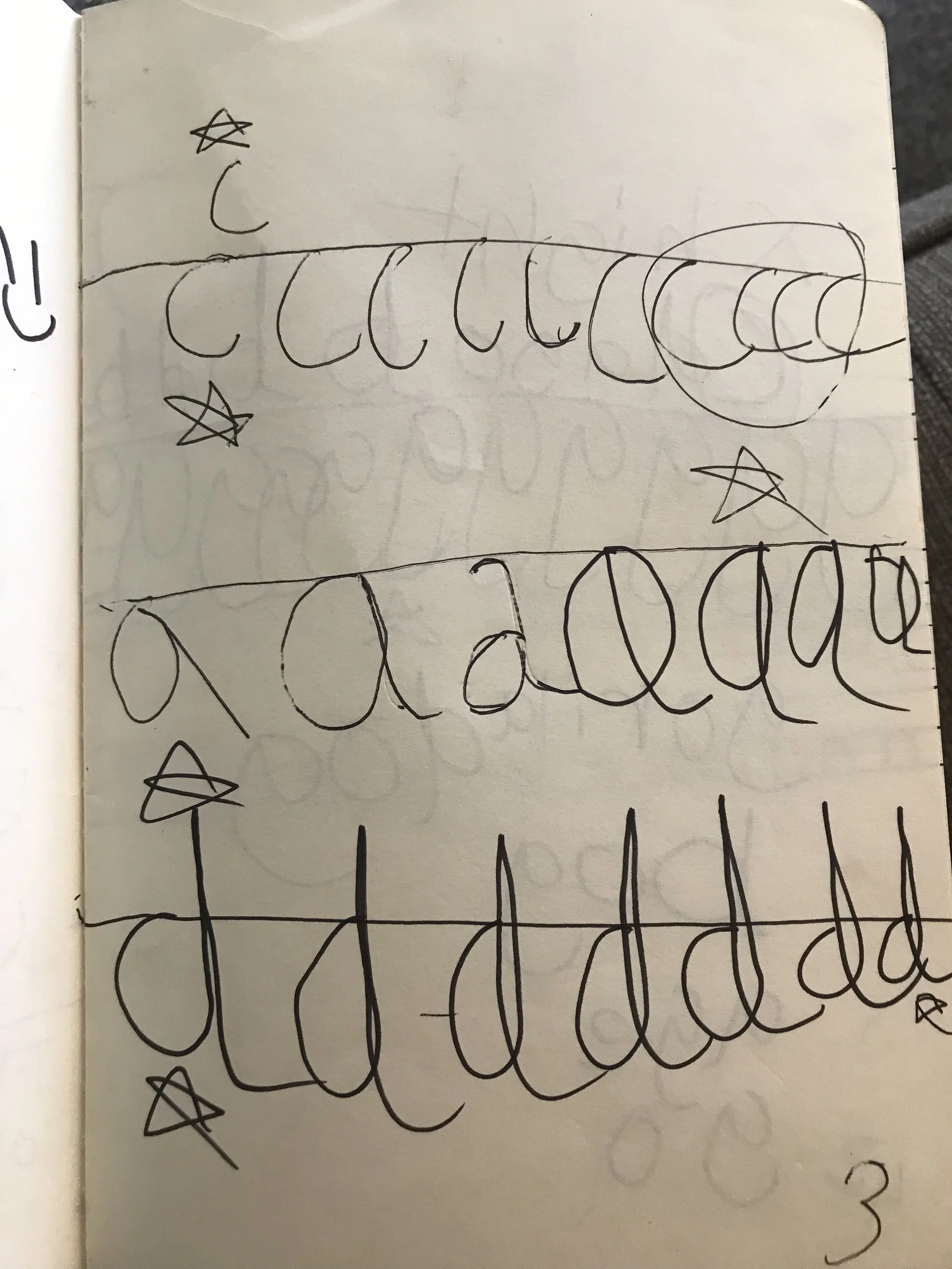

Encouraging Self-Reflection

A strategy that really motivated my students to practice letters and graphemes multiple times was to put a star by their “favorite.” This calls their attention to their own writing and lets them compare their own work in a non-judgmental way. They are starring the letter they like best, not the one that most closely follows an arbitrary standard. This also encourages them to focus on the positives in their own writing. When using this strategy, some of my students had difficulty drawing a star. One of my students fixed this problem by using smiley faces and hearts instead. Another student asked for my help and we spent around 10 minutes of a session practicing the “pathway” for the 5-pointed star. This ended up not only being a confidence booster for this student, but also a great way to ground the Real Script concepts we’d been discussing in something personally relevant.

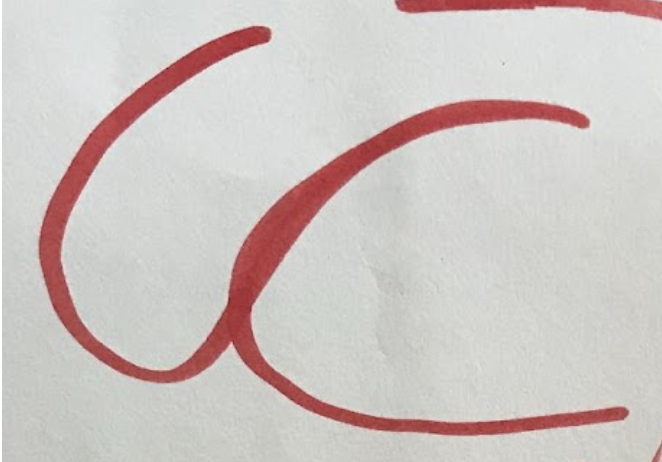

Providing Scaffolding

Some of my students have had an issue remembering letter pathways while ligaturing, especially when ligaturing into letters in the <c> emblem. Because letters in the <c> emblem start on the right and move left first, students tended to ignore the learned pathways and start these letters from below, often leaving no space between the ligatured letters. This was an issue for students even after practicing <c> emblem pathways several times. I’ve found that it’s helped to practice the pathways first separately and then practice ligaturing on the same page so that students have a reference nearby. It also helps to break the ligaturing process into manageable steps and practice each one in sequence. I’ve found that the pathway from the exit stroke of one letter to the entrance stroke of another is the most challenging for students since it is not consistent; it changes depending on both connecting letters. Some of my students found it useful to practice ligaturing c’s together before trying any other pathways in the <c> emblem. One student noted that it looks like waves when multiple c’s are ligatured together, and this was a helpful verbal reminder for her.

Giving Students Voice and Choice

One challenge that I hadn’t expected was the vehement dislike many of my students had for handwriting instruction, or handwriting in general. Most of my students associated handwriting lessons with strict or mean teachers, repetitive drills, and feeling shamed. To make our practice seem less repetitive and reminiscent of drills, I encouraged students to generate words on their own to write. To make sure they were practicing the pathways I wanted them to, I would use letter tiles to remind students which letters had already been introduced and let them rearrange the tiles to make words. Once they found a word, they rewrote it by hand. This allowed them to feel like they had some agency in what they were writing.

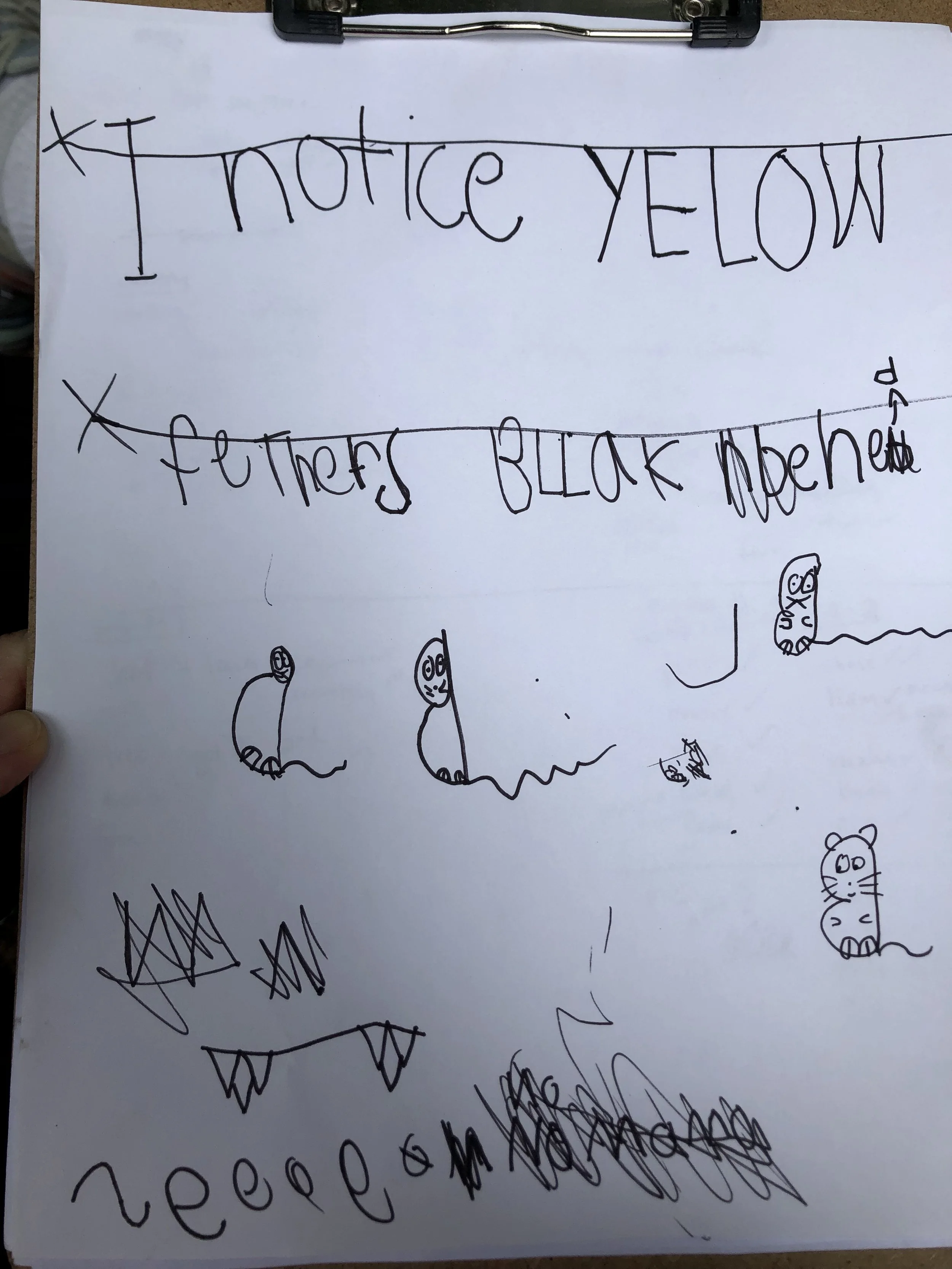

Research Outcomes

Since this was a short study, I did not expect my students to show dramatic changes in their handwriting. However, some students minimized their reversed letters by the end of the intervention, and one student in particular was noticeably more fluid in her writing. The most significant change was the students’ attitudes towards writing. At the start of the study, all of my students were very vocal about disliking handwriting. By the end of the study, most of my students viewed writing in a positive light (one was decidedly neutral). One student was especially against anything close to cursive at the beginning due to a particularly harsh teacher, but had completely switched to loving ligaturing and trying out personal signatures by the end.

At the end of my study, I asked each of my students for their perspective on the intervention and how it affected them. Two of my students said they gained confidence in their writing. Another said she felt like she was a better speller. Since I did brief pre- and post-assessments, I was able to note that her spelling really did improve - for example, she spelled <quick> as <qwik> in the pre-assessment, but spelled it correctly in the post. This suggests that the work we did practicing and ligaturing graphemes (like the digraph <ck>) did help her, at least for this example. I also asked students for their favorite parts of the intervention: creating/practicing their signature, drawing stars, practicing ligaturing/cursive, and playing games (especially Finish the Face).

Since I worked with students individually for this intervention, I was able to see how Real Script can adapt to fit the needs of different students. With some, we focused much more on specific letter pathways and with others, we focused on ligaturing or writing words. I also learned how much students value teachers being vulnerable and admitting they are learning and making mistakes as well. Most of my students were much more willing to try things out if I was trying them too.

Framing things as experiments really helped to get students engaged, whether we were testing out different sitting postures, writing utensils, or writing styles.

As more educators implement Real Script, I urge them to prioritize students’ comfort and legibility over neatness and uniformity. I think one of the biggest strengths of this program is that it allows students to find their own style without shame or judgment. It’s important to keep in mind that a program like Real Script works best when it’s introduced and practiced frequently and consistently over a long period of time. Additionally, I think that Real Script benefits from use in conjunction with other subjects as well as with students’ personal interests. This way, handwriting stays relevant and interesting for students rather than something they are forced to do without a reason. I hope my journey encourages other tutors, teachers, and educational therapists to give Real Script a try!

About the Author

Leah Mills is a second year Teaching Fellow at Words in the Wild. She is a graduate student in the Educational Therapy program at Holy Names University. She graduated with a B.A. in Deaf Studies with a concentration in Education from CSU Northridge. She is passionate about making education accessible and engaging to all students and incorporating students' strengths and interests into their learning.